Zena Marpet was apprehensive, as we've all been, wondering if her personal plans were worth the risk of exposing herself and others to the invisible menace that's disrupted and threatened our lives for the last 11 months.

The safest, smartest plan would be to stay home in California and watch on TV. The COVID-19 vaccination she'd already received as a health care worker provided some solace but no guarantees for her and those she'd be around.

She and her family have been so careful during the pandemic. Now, though, a rare opportunity presented itself.

How many times do you get to go to the Super Bowl?

More specifically, how many times do you get to go to the Super Bowl ... to watch your brother play ... in his team's home stadium ... in the area that's become your family's second home ... where your parents migrated when you and one of your older brothers went to college there ... and where one of your other brothers, the one participating in America's biggest game, was drafted to play, as if by fate?

When will you get to experience this all again?

When is the last time you even saw your family?

Zena pondered all of this and more, even as she sat at the gate at Fresno Yosemite International Airport on Wednesday, awaiting the first leg of her cross-country trip to Tampa, Florida.

"I was super-conflicted, but I'm incredibly excited to connect in person and just be together," she said by phone, about 45 minutes before her flight was scheduled to board. "We always say when we get together, it's madness, but we're going to 'visit.' Just gathering, talking and catching up for hours, even if we do absolutely nothing."

Oh, they're doing something.

The Marpet family will attend Super Bowl LV between the Kansas City Chiefs and Tampa Bay Buccaneers on Sunday at Raymond James Stadium in Tampa -- the culmination of a season unlike any other in NFL history. It will be a celebration of football, as well as the people who helped the league, the players and everyone else get here. The NFL has given 7,500 vaccinated health care workers free tickets and has named Suzie Dorner, a nurse manager at Tampa General Hospital, an honorary captain for the game.

In much the same way, the Marpet family will be celebrating the achievements of their two youngest children:

- Zena, an emergency room nurse at Kaweah Delta Medical Center in Visalia, California, a hospital that has been so overrun with COVID-19 patients that Zena and her colleagues are treating some of them in the hallways;

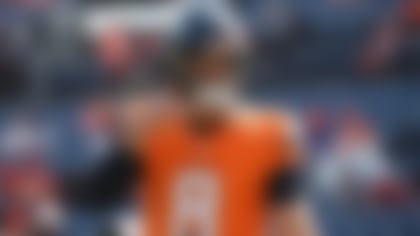

- And Ali Marpet, the Buccaneers' starting left guard, who began his NFL journey as an unassuming, determined, small-school lineman from Division III Hobart College just hoping to make a roster or a practice squad one day, and is now halfway through a $54 million contract and blocking for Tom Brady in the damn Super Bowl.

The Marpets are proud of what their children have done -- one between the white lines and the other on the frontlines. And for the first time since they spent the 2019 holiday season together, they get to tell all of their kids how much they love them in person.

At the Super Bowl.

"It's huge. It's a little overwhelming," said Bill Marpet, father to Zena, Ali and their two older brothers, Blaze and Brody. "The whole separation that's been mandated by COVID makes the moments you have together that much more precious and important. I really have to stay over my feet, stay in the moment and just try to enjoy everything."

* * * * *

All of the Marpet children are close, though Ali and Zena have a unique connection, because they're separated by just over a year (Ali is 27, Zena 26). They were the last two children in the house when Blaze and Brody went to college, and their groups of friends overlapped. The Marpets had a big, welcoming home in Westchester County, New York, that served as a place where everyone could gather for a safe, enjoyable time.

"People just want to be around Ali. He didn't even use his cell phone; people just showed up," Zena recalled. "My mom used to joke Ali is so big he has his own gravitational pull, like a planet."

All of the Marpet boys were big, leading to many jokes about when the petite Zena would round into football shape.

But while her brothers played sports in high school, Zena had other interests. With Bill being one of the preeminent fashion videographers in the country, she initially wanted to follow in his footsteps, albeit with a selfless angle to combat the unrealistic body standards of the industry. "A love-the-way-you-look kind of thing," as Bill describes it.

That's the kind of person Zena has always been: The responsible one. The designated driver. The one at parties who made sure the freshmen didn't get too tipsy.

There's a unique loneliness and isolation when you're in health care. ... There's no way to convey the madness and the darkness of some of the heartbreaking and intense situations we're in. Zena Marpet, ER nurse

In her junior year in high school, Zena was diagnosed with ulcerative colitis, a bowel disease that results in chronic inflammation in the digestive tract. Between that and the fact that her mother, Joy Rose, is a lupus survivor who underwent a kidney transplant, Zena was aware of the positive impact a medical career could have.

She got involved with emergency medical services and ambulance work in high school. In college at Eckerd College, she became an EMT and was a part of a collegiate emergency response team.

"I knew I had three boys that were adrenaline junkies, but I didn't know I had a daughter like that, too," Bill said with a laugh. "She'd say, 'Oh, Dad, we found this guy, he fell out of a tree, 30 feet, and the bone was sticking out of his leg and we stuck it back in.' And she's talking about it matter-of-factly, as if she went shopping."

It's possible the numerous trips to the ER for the Marpet boys when roughhousing went awry prepared Zena for some of the gorier things she'd see on the job. Like the time Ali had a piece of lead stuck in his arm after one of his brothers stabbed him with a pencil. Or when Ali had a LEGO stuck in his head and needed to have it dislodged.

"I'd like to think my brothers and I had a hand in that," Ali said with a laugh when asked about Zena's toughness. "Just every day, you have to have thick skin because we did not take it easy on her."

Of course, Bill and Ali know health care is about more than just a rush for Zena. It's deeper than that.

"People always ask, 'Why nursing? Why do you do this?' It wasn't a choice. It chose me," Zena said. "And I feel that so deeply. There's no other thing I could possibly be doing."

* * * * *

There's no other thing Ali could possibly be doing, either. That's the way his friends and family see it. The young man is all about football, all the time.

Bill has yet to even meet Brady (thanks, COVID), though he imagines he's a lot like his son. The way he describes Ali is, if they were out together somewhere, and there were two sets of stairs leading up to a building, Ali would probably think to himself, "Which set would make me a better football player? That's the one I'm going to take."

Yeah, that sounds exactly like Brady.

Speaking of Brady, he signed with the Buccaneers in March of last year, right as the pandemic began. Ali finally got the chance to meet him a few weeks later. Brady had done his homework on the key players on the teams he was considering signing with in free agency, so he had noted the consistency of Marpet, who was Pro Football Focus' seventh-ranked guard this past season (min. 100 snaps) and currently has a streak of 26 games without allowing a sack (including playoffs).

"I think you're a really good player," Brady told Marpet.

"You're not so bad yourself," Ali shot back.

Shortly thereafter, Rob Gronkowski joined the party as well. A potentially Super team -- capital "S" -- was forming.

"COVID had hit, the Brady thing happened and then Gronk, and I'm just thinking, This isn't real life. Things are just too weird, too surreal," Zena said. "I just gave up trying to process it mentally. It was too much."

That's kind of how Zena, her coworkers and frontline workers across the country had to cope with the pandemic. Zena was working at a mental health facility at the time, and she says she was pulling 70-hour weeks. Her family was concerned from afar, but like the patients she was treating, Zena had to deal with it alone.

Adding to her frustration was the fact she was planning to move back to the Tampa area; because she and Blaze had studied at Eckerd College (which is in St. Petersburg, Florida), her parents had established a part-time residency in the region. With Ali playing for the Bucs, she figured moving back would bring most of the family together again. However, the pandemic put her relocation plans on hold.

There were also days she wondered how cushy and comfortable life would've been if she'd chosen another career path -- perhaps those fashion media jobs she'd initially eyed while dreaming of following her father's path.

Those gigs don't require you to be there when a patient realizes he or she might be dying of an affliction they never thought would affect them. For Zena, it's equal parts burden and reward.

"It's a privilege to be there for someone's vulnerable moment where it hits them. That's the special thing with nursing," she said. "We're a cohesive team with the doctors and techs and every single person involved in the case, but everyone sees the intimacy we have with patients, and it feels like that's really respected."

* * * * *

Still, it has worn on Zena and every frontline worker.

Feeling burned out in August, she took a break from health care for a little over a month and returned in October reinvigorated, taking on an ER role just in time for a big surge of COVID patients.

If anybody in the family understood Zena's plight, it was Ali. Bill says Ali and Zena have similar personalities in that they don't "raise their own flags at all" to let others know if they're struggling. Instead, he likens it to Ali wanting to just work hard and dominate the guy across the line from him.

"I agree with my dad on that. She's not going to tell you how hard something is," Ali said. "She's just going to show up and grind it out. But I knew she was having it rough."

Zena had told Ali their days off were similar -- resting their bodies and minds, getting just enough of a recovery in time to do it all again.

That's when they would actually communicate directly. Most of the time, because both work long days on opposite coasts and go radio silent while doing so, their schedules didn't align. So they'd send funny memes and TikToks for the other to discover after work ended, knowing both of them could use a laugh to decompress from their stressful jobs.

It's as close as anyone could get to understanding the pressure and stress Zena faces on a daily basis.

Just like no one understands how hard it is to block someone like Chiefs defensive lineman Chris Jones, whom Ali will face on Sunday.

"There's a unique loneliness and isolation when you're in health care," Zena said. "You can tell the stories, but there's no way to really convey it to people who aren't in this field. It's like this dark cloud that's always with you. There's no way to convey the madness and the darkness of some of the heartbreaking and intense situations we're in.

"Health care workers need to really focus on taking care of themselves, and whatever that looks like for them."

* * * * *

For Zena, that's meant getting time outdoors in her downtime in California's multitude of parks. It also meant boarding that flight to head to Tampa, knowing there were no guarantees she, her family or anyone they encounter in the coming days will remain COVID-free.

Ali said when he sees his sister, everyone will be outside and masked up, and not just before the game. In the days afterward, they'll continue to exercise caution. For the Marpets, it's not just about making sure Ali and his teammates are available to play on Sunday. It's about staying safe, period.

Through Zena's work, they've all had a greater appreciation and respect for frontline workers and the virus they're combating.

"It puts everything in perspective for me," Ali said. "When guys would complain about anything -- being masked up or the testing protocols -- I feel we have nothing to complain about. I feel very fortunate we have the tools and resources to do everything we're able to do.

"The stuff we go through is not hard compared to what people are going through."

Follow Mike Garafolo on Twitter.